It was time for all things Scottish at the Pacific Symphony on Thursday night, and in case anyone forgot, there was a kilted piper wailing away on the plaza in front of Segerstrom Concert Hall, giving us “Scotland the Brave” and other greatest hits of the bagpipe.

The enthusiasm was echoed inside, although the concert, which continues through Saturday, included the work of only one bonafide Scotsman. Ironically, the bulk of the program was provided by a couple of Germans, Felix Mendelssohn and Max Bruch, and presided over by an Austrian, guest conductor David Danzmayr. But any son or daughter of Scotland would have been proud of the result.

The short concert opener, Hamish MacCunn’s “The Land of the Mountain and the Flood,” is a charming and frolicsome bit of highland horseplay – much better than that derivative pastiche that George Bernard Shaw described in his withering review (he was Irish, which explains a bit). It’s full of proud trombone announcements, folksy melodies passed back and forth through the strings, and a rousing, extended ending worthy of Beethoven. MacCunn died fairly young, and he’s not well known outside of his native Scotland, but he clearly had mastered the craft of late Romantic symphonic writing.

Bruch’s “Scottish Fantasy” for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 46, was a revelation. Bruch was an under-appreciated composer who outlived the late Romantic era, where his style is firmly fixed. He never went to Scotland, but that didn’t stop him from writing a thoroughly Scotch-sounding work, full of affecting melodies based on Scottish folk sources.

It’s a finely crafted piece full of long-lined melodies, and violinist Ning Feng made them sing. His sound is sweet, burnished and perfectly controlled, with a gorgeous pianissimo that is feathery but distinct. There are plenty of opportunities for rollicking triple stops and high-velocity showmanship, though, in the final movement, marked Allegro vivacissimo – as fast and lively as possible. Feng gave us more of his gorgeous, limpid tones in his encore, the Largo from J.S. Bach’s Sonata No. 3 in C Major, BWV 1005.

Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 3 in A Minor, usually called the Scottish, was the main event, and it was a showcase in several respects. The woodwinds were a standout; principal clarinettist Joseph Morris had a stellar night with a memorable solo. The strings were lucid and pure in the first movement, and their sense of ensemble was impeccable in the faster second and fourth movements.

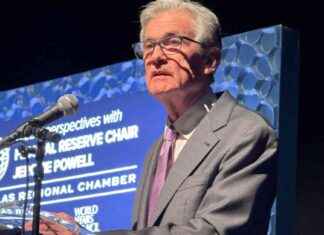

The biggest source of enjoyment, though, was Danzmayr. Compact and energetic, he’s a fascinating conductor to watch. He was masterful with the constantly changing speed of the work’s first movement, and his tempo choices always seem intrinsically right. His arm movements are large yet economical, and his dynamic can change on a dime, carving space in huge arcs with his arms then pulling the ensemble into a sudden pianissimo with a sharp, precise contraction of his hands.

Danzmayr was assistant conductor of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra; he seems to have the land’s music in his blood. As Mendelssohn and Bruch proved, you don’t have to be Scottish to make music like a native.

Contact the writer: 714-796-7979 or phodgins@scng.com

Our editors found this article on this site using Google and regenerated it for our readers.