In the animal kingdom, many species have developed specialized organs for catching prey. And when it comes to frogs, it is their stretchable tongues. But there is a lot more to how these amphibians use it to snag insects, especially the unique nature of their saliva, as researchers explained in a new study.

Human saliva is over 99 percent water, and not really sticky. Frog saliva, on the other hand, can be thicker than honey and really sticky. But that consistency is not constant because it can rapidly lose its viscosity and turn watery as well, all in a matter of a couple of seconds.

Explaining the changes in frog saliva when it is catching prey, Alexis Noel, a Georgia Tech mechanical engineering PhD student who led the study, said in a statement Tuesday: “There are actually three phases. When the tongue first hits the insect, the saliva is almost like water and fills all the bug’s crevices. Then, when the tongue snaps back, the saliva changes and becomes more viscous — thicker than honey, actually — gripping the insect for the ride back. The saliva turns watery again when the insect is sheared off inside the mouth.”

A frog’s tongue, the other component of its hunting mechanism, is also quite remarkable. It is made up of tissue that is as soft as the brain, or about 10 times softer than the human tongue. It Fenomenbet can stretch to great lengths, several times the size of the frog’s mouth, and its tissue also absorbs the shock generated by the speed at which the tongue shoots out the mouth and is retracted (the force with which the frog’s prey is hit by its tongue is five times great than gravity).

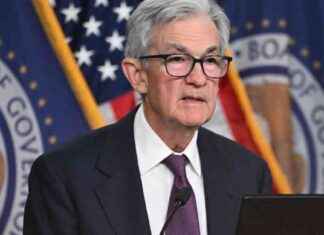

A northern leopard frog grabs a cricket. Photo: Candler Hobbs/Georgia Tech

“The tongue acts like a bungee cord once it latches onto its prey. It deforms itself as it pulls back toward the mouth, continually storing the intense applied forces in its stretchy tissue and dissipating them in its internal damping,” Noel explained in the statement.

The change between the different consistencies of frog spit cannot be noticed even in slow-motion videos. Noel reached her conclusions after studying spit samples from 18 frogs in a rheometer, a device for highly sensitive measurements of fluid properties.

David Hu, a professor at Georgia Tech and Noel’s doctoral adviser, spoke about how the study could find practical applications.

“Most adhesives that have been created are stiff, especially tape. Frog tongues can attach and reattach with soft, special properties that are extremely stickier than typical materials. Perhaps this technology could be used for new Band-Aids. Or it could be used to create new materials in soft manufacturing,” Hu said.

The study, titled “Frogs use a viscoelastic tongue and non-Newtonian saliva to catch prey,” is published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Our editors found this article on this site using Google and regenerated it for our readers.